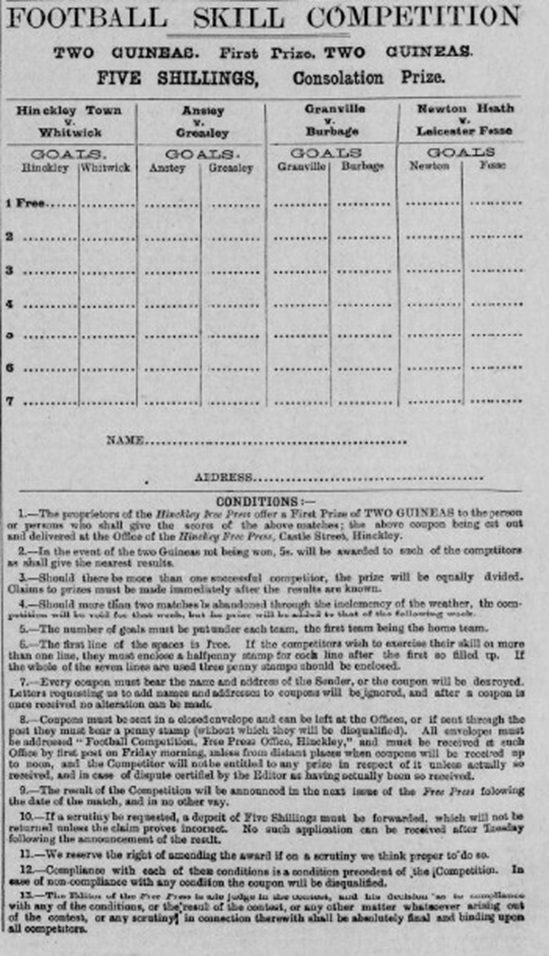

Competitions for predicting the results of football matches are as old as competitive football. The Hinckley Times newspaper, for example, throughout the 1898-99 season, offered a premier prize of two guineas to “the Competitor who predicts the results” of four football local matches to be played the following Saturday. Readers were invited to cut out and fill in a coupon printed in the newspaper, which had to be sent to the newspaper’s offices by the Friday before the matches. Should there be more than one winner, the prize was equally divided. If more than 2 matches were abandoned the prize money was added to that of the following week. In the event of no one predicting all four scores, a consolation prize of 5/- was awarded to the closest entry. The first entry was free. For each additional entry competitors had to add a half penny stamp with their entry. If all seven lines were filled a 3d stamp had to be enclosed. The outcome and winner was announced the following week.

Coalville Time ran a similar competition, with a first prize of 10 shillings.

Football Pools did not arrive for another 20 or so years. It was thought up in the early 1920s by John Jervis Barnard, from Birmingham. He noticed that most of his friends liked football and placing bets but at the time betting was only legal on racecourses, so he came up with the idea of punters guessing the outcome of matches and collecting their winnings from the pool of stake money – which is where the name “Pools” came from. John Moores, a Post Office messenger from Liverpool with get-rich dreams, saw potential in the idea and took it back to his home town of Manchester where he and two workmates Colin Askham and Bill Hughes each invested £50 in the scheme. They bought a cheap printing press, rented an office on Church Street in Liverpool city centre and named their business Littlewoods. They printed off 4,000 coupons and handed them out at Manchester United’s Old Trafford ground on a match day in 1923 – but only 35 were returned and the three didn’t even cover their expenses. In the middle of the following season, with the project continuing to lose money despite them having invested another £150 each, Hughes and Askham wanted to give up, but John Moores held his nerve and bought them out. It was a gamble that paid off hugely – when he died in 1993, aged 97, he was estimated to be worth more than £1 billion.

Vernons’ Pools was founded in 1925, also in Liverpool, and Zetters was founded 1933 in London. By 1936, revenue from the 28 pools companies had reached almost £30 million per year, and the pools accounted for four million out of six million postal packets sent weekly in the UK.

The Treble Chance game began in 1946. Players were given a list of football matches set to take place over the coming week and attempted to pick a line of eight of them, whose results would be worth the most points by the scoring scheme; traditionally by crossing specific boxes on a printed coupon. A proportion of the players’ combined entry fees was distributed as prizes among those whose entries achieved the highest scores. Prior to this the Penny Points and Penny Results were the most popular games. The Treble Chance offered a potential large jackpot at a time when no other form of gambling in the United Kingdom did. Some pools offered additional ways to win, based on scores of football matches at half-time, or football matches in which a particular number of goals were scored.

Although competition from the National Lottery led to a rapid fall-off in players the pools are still going strong today. You can play the classic version of the game online, as well as several other options.